Spelling Synergetics Part 1: The Abacus

- Dante Michael

- Dec 9, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Dec 16, 2025

I had a sudden realization about halfway through David Abram's magnificent book, The Spell of the Sensuous (1997). Why didn't anyone teach me that the alphabet is a technology? I memorized the ABCs so early in life that I never seriously questioned the origin of its symbolism. What are these occult letters - nothing but scribbles on paper (and screens) that designate sounds? There is, indeed, a certain magical effect behind written symbols, which is still conveyed in the meaning of 'spell', or "to step under the influence of the written letters ourselves, to cast a spell upon our own senses." (p.84) Phonetic writing systems caused such a profound change in human awareness that we can hardly remember what life was like without them. I want to replicate that process - that spellling - for Buckminster Fuller's Synergetics. It begins with an investigation of how cultural evolution is shifted (punctuated) by conceptual technologies like the alphabet, which shifted us from oral to literate culture:

The written character no longer refers us to any sensible phenomenon out in the world... but solely to a gesture to be made by the human mouth. A direct association is established between the pictorial sign and the vocal gesture, for the first time completely bypassing the thing pictured. The evocative phenomena - the entities imaged - are no longer a necessary part of the equation. Human utterances are now elicited, directly, by human-made signs; the larger, more-than-human life-world is no longer a part of the semiotic, no longer a necessary part of the system... With the advent of the aleph-beth, a new distance opens between human culture and the rest of nature. -The Spell of the Sensuous (66-67)

This new distance is cause for concern but David remains optimistic. My personal fascination lies in how pictorial signs initially transformed human consciousness. How exactly did the alphabet 'upgrade' our phenomenology? We can trace a path through language to understand how we got here. The philosopher Edmund Husserl described a "concealed historical meaning" of the "sedimented conceptual system that every philosopher takes for granted." (The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology, p. 71) The indifference of natural science to the "life-world" of subjective experience is the pernicious cause of the meaning crisis. And by studying language - written and spoken - we can diagnose this cultural malaise by "making the teleology in the historical becoming of philosophy [comprehensible]." Nothing is guaranteed by these assertions; they are conjectures as to why and how the phonetic alphabet could be so transformative. Abram explores Husserl's thought at length because it highlights "the importance of the earth for all human cognition." (p.35)

Another inspiration for Abram is Marshall McLuhan, who achieved worldwide fame in the 1960s for his studies of media. I recently digitized a VHS documentary about McLuhan and can confirm that his message (the 'medium') has aged like wine. He argued that television, like radio, is an acoustic medium. What you watch on TV is essentially irrelevant compared to the phenomenological shift caused by the medium of television itself. Just as the wheel is an extension of the human foot, so are electrical circuits extensions of the human nervous system. The detached visual media of letters and books are now challenged by instant global communications, moving us into a post-literate society of total involvement (a global village). McLuhan was declaring the return of tribal thinking, which brings literacy under intense scrutiny on account of its detaching and schizophrenic effects. Most people lose the thread of McLuhan's argument because they fail to grasp (or have simply forgotten) the natural magic of writing as a technology. So how could they possibly appreciate what he had to say about television?

The interiorization of the technology of the phonetic alphabet translates man from the magical world of the ear to the neutral visual world. A child in any Western millieu is surrounded by an abstract explicit visual technology of uniform time and uniform continuous space in which 'cause' is efficient and sequential, and things move and happen on single planes and in successive order. But the African child lives in the implicit, magical world of the resonant oral word. ...Since the ear world is a hot hyperesthetic world and the eye world is a relatively cool, neutral world, the Westerner appears to people of ear culture to be a very cold fish indeed. -The Gutenberg Galaxy (19)

Like McLuhan (a fellow Canadian), I belong to the Western tradition. This is my tribe within the global village, which explains why I'm so curious about the subversive effects of the alphabet. Here is a technology that was embedded in my consciousness and has irrevocably shaped my understanding of communication as a whole: reading books, writing emails, talking on the phone.

Are the ABCs actually causing me to be disengaged from nature?

Could the phonetic alphabet truly be linked to the disenchantment of the world?

And if so, then what the hell could I even do about it?

phonetics ~ the acoustics of speech.

fə-ˈne-tik ~ the International Phonetic Alphabet spelling of 'phonetic'.

The English alphabet is phonetic—that is, the letters represent sounds.

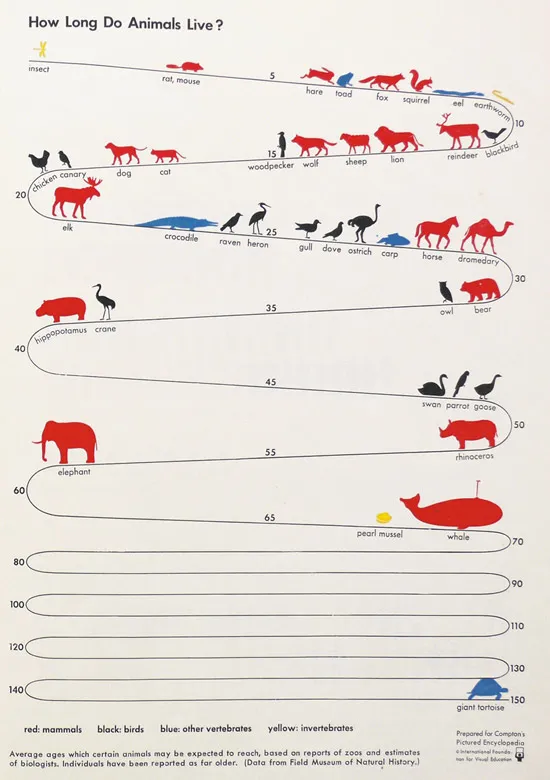

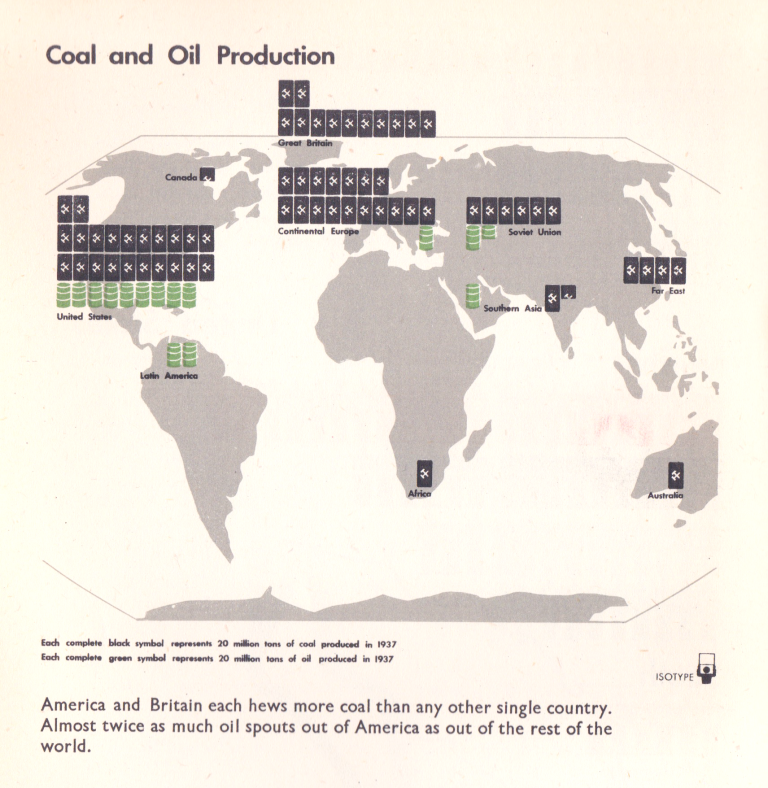

The Chinese alphabet, however, isn't phonetic, since its symbols represent ideas rather than sounds. -Merriam-WebsterOne could spend a lifetime plumbing the depths of language. My particular focus is on the pictorial representations themselves, which are simply the visual markings we find on any such surface as paper, dirt or a comptuer display. Firstly, these traces are always geometric, meaning they have a physical presence with measurable dimensions. Secondly, like Chinese, they can represent general ideas instead of particular sounds. There is ample historical evidence telling us about different ways of combining words and pictures. A good example is the rebus (top left), where icons replaced a phoneme or syllable. Emblem books (top middle) were popular in Early Modern Europe and combined philosophy and poetry with allegorical illustrations. The Kabbalah (top right) linked the 22 leters of the Hebrew alphabet with 10 Sefirot into 32 paths of wisdom. Finally, the pictographic language known as Isotype (bottom row) was developed by the philosopher Otto Neurath in the 1930s. Neurath was famous for his role in the Vienna Circle and wrote influential pieces on science and language. He was inspired by Egyptian hieroglyphics, perhaps in subtle recognition of the coming tribalization of the global village. Neurath wrote: "communication of knowledge through pictures will play an increasingly large part in the future." (From hieroglyphics to Isotype: a visual autobiography, p.5)

Anyone familiar with Buckminster Fuller will have a special appreciation for 'the communication of knowledge through pictures'. There are a total of 311 illustrations across both volumes of Synergetics and many more to be found in Fuller's other works. Some of his diagrams resemble Isotype by using familiar objects to explain abstract ideas. But the vast majority of them are pure geometric figures: perfect sphere-packing, isometric triangulation, polyhedral hierarchies. Yet Synergetics is not a book of pure mathematics, as evidenced by its subtitle, 'The Geometry of Thinking'. The images in Synergetics should be read as the 'linguistic markings' of Bucky's own thinking insofar as they could represent sounds (like English) or ideas (like Chinese). I'm trying to explain that a phonetic technology is operating in Synergetics that has less to do with the vocal gestures of the human mouth than with the acoustic medium as such. It requires "using the eye as an ear, not as an eye", as McLuhan said about television. Sound, as radiation, is totally involving and omnidirectional; the very phenomenology modeled by Fuller's thought (omnitopology). However, the pictures in Synergetics are not irrelevant just because they are flat, abstract and merely visual. These images represent the characters of a language (Bucky called it the language of electromagnetics). And like an electric circuit, this language doesn't just sit 'out there' on the page but actively pushes you in.

A triptych from McLuhan's book "Counterblast" (1969), pages 14, 15-16.

The Book of Nature metaphor has been around since the time of Augstine in the 4th century AD. It became hugely popular once the printing press made books ubiquitious from the 15th century onward. While it's hardly the 'new metaphor' that McLuhan wanted (above left), it fits Synergetics like a glove. The metaphor of Nature-as-Book hinges on the difference between seeing markings scattered across a page and reading them as a language; between perception and comprehension. Imagine giving a book to a pre-literate human. The letters would appear as so many scratches and scrapes on a rough surface. They would see but they would not comprehend. Looking with the eyes is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the phonetic alphabet (as it is for geometric figures in general). In fact, all of the human senses must be recalibrated and "trained" before the mind can employ conceptual technologies 'animistically'.

In the oral, animistic world of pre-Christian and peasant Europe, all things - animals, forests, rivers, and caves - had the power of expressive speech, and the primary medium of this collective discourse was the air. In the absence of writing, human utterance, whether embodied in songs, stories, or spontaneous sounds, was inseparable from the exhaled breath... the progressive spread of Christianity was largely dependent upon the spread of the alphabet... one had to induce the unlettered, tribal peoples to begin to use the technology upon which that faith depended. Only by training the senses to participate with the written word could one hope to break their spontaneous participation with the animate terrain. Only as the written text began to speak would the voices of the forest, and of the river, begin to fade. And only then would language loosen its ancient association with the invisible breath, the spirit sever itself from the wind, the psyche dissociate itself from the environing air. The air, once the very medium of expressive interchange, would become an increasingly empty and unnoticed phenomenon, displaced by the strange new medium of the written word. -The Spell of the Sensuous (151-152)

By this point in Abram's book, I was feeling a shade of despair. It seemed that humans had severed their connection with the animate earth millenia ago, making us helpless victims left to suffer the consequences. But there is always hope if we know where to find it. Abram wrote his book as a story that "makes sense", i.e. "one that stirs the senses from their slumber, one that opens the eyes and the ears to their real surroundings" (p.158). The Spell of the Sensuous is a story about the natural magic of writing... and it makes sense! The alphabet didn't unleash maleficent entites that corrupted our innate connection to Nature; they work as natural extensions of our senses and so retain their animating power. The Book of Nature is still a relevant metaphor because it reminds us that literacy transmits life. We have every reason to believe - as any natural scientist must - that the story in the Book of Nature makes sense.

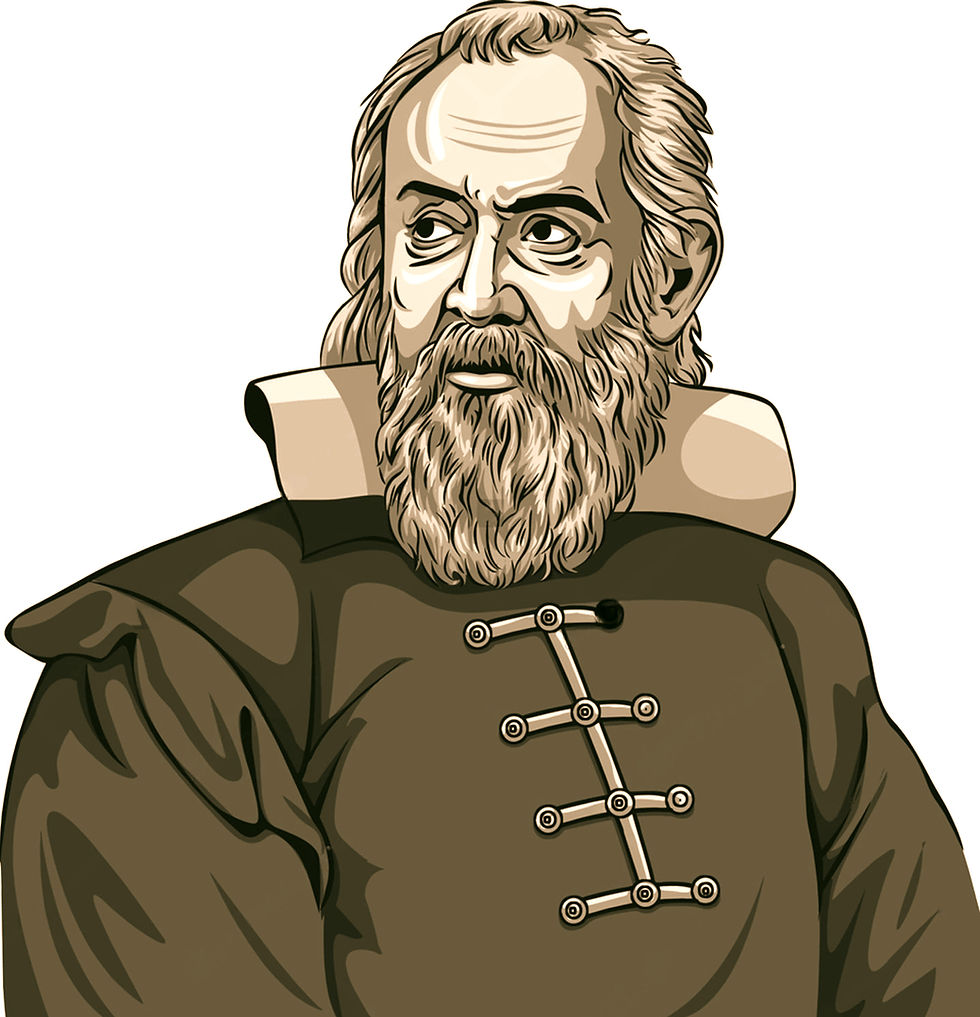

Philosophy is written in this grand book—the Universe—which stands continually open to our gaze, but it cannot be understood unless one first learns to comprehend the language and interpret the characters in which it is written. It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometrical figures, without which it is humanly impossible to understand a single word of it; without these, one is wandering around in a dark labyrinth.

Galileo Galilei (1564-1642)

The Assayer (1623), p. 25

Galileo's version of the nature-as-book metaphor has stood the test of time. It highlights the central importance of method, or why comparing the natural world to a book makes any sense at all. How do we know that humans can actually comprehend a purely mathematical language? Triangles and circles can't be read off the page like the strokes of the Hebrew aleph א. Yet these geometric figures inhabit the same visual media that our senses have been trained to participate in. They appear on your screen, animated right alongside English words and letters. Like any pictorial sign, we can point to them and study them over time. What is their meaning? The answer is determined by the method we use to comprehend them. We can stare at these figures endlessly without actually reading them at all. If I were to revitalize the nature-as-book metaphor for today, it would read:

The Book of Nature is a picture book

and its story is about technology.The diagram below is from Fuller's Synergetics - it's official title is 'Underlying Order in Randomness'. It first appeared in Utopia or Oblivion (1963) where Fuller wrote on page 72: "I find this chart to be one of the most exciting I've been able to put on paper."

I've puzzled over this chart for more than a decade. How could something so simple be so exciting? Now, with the catching of these cosmic fish, I've finally discovered why. I first conjectured that this chart was Fuller's alphabet, like a private numerical lexicon. The problem is that there are no phonetic instructions here, no direct association between the pictorial representations and a set of vocal gestures or sounds. Recall that the phonetic alphabet allowed us to "bypass the phenomena" by connecting human-made signs with human-made sounds. Fuller's chart connects human-made signs to the natural phenomena themselves as a priori relationships between things. The closest historical tool that worked like this is the abacus.

abacus ~ a tool for performing calculations

etymology: Middle English, from Latin, from Greek abax, abak-, counting board perhaps from a Semitic source akin to Hebrew 'ābāq, dust

Originally, the abacus was, in fact, dusty. The Greek word abax has as one of its senses: a board sprinkled with sand or dust for drawing geometric diagrams. This board is a relative of the abacus familiar to us. American Heritage DictionaryThese are Fuller's drawings in the sand. Do they make sense? Stay tuned.

About the Author:

Dante Diotallevi is an independent scholar living in Canada. He holds a BSc. in Biology and an M.A. in Philosophy from Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario.

Comments