Spelling Synergetics Part 2: Figure and Ground

- Dante Michael

- Dec 22, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 6

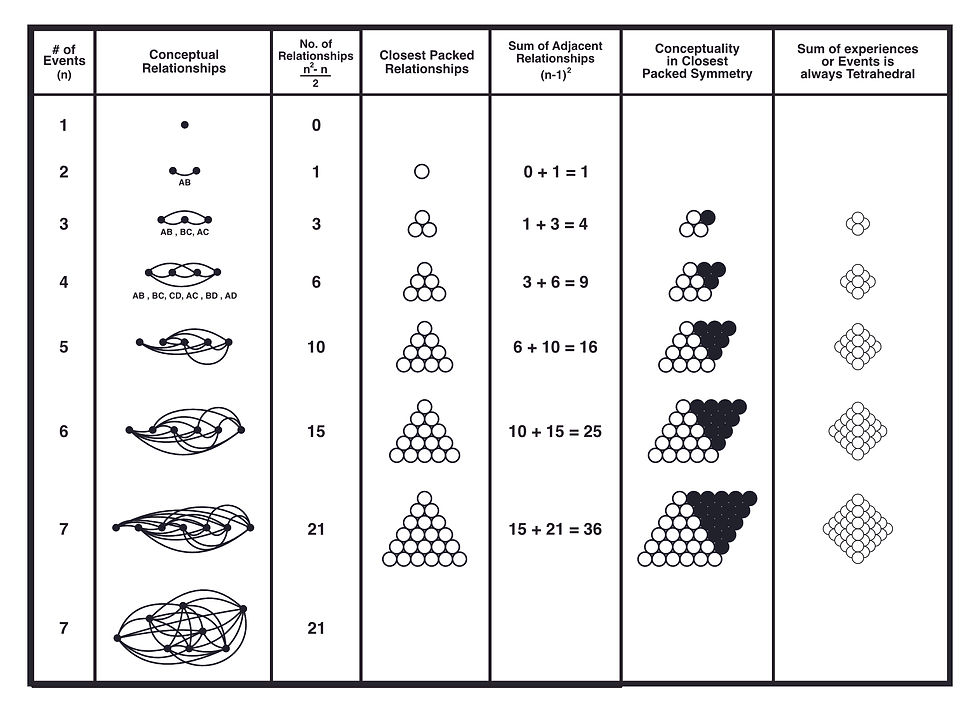

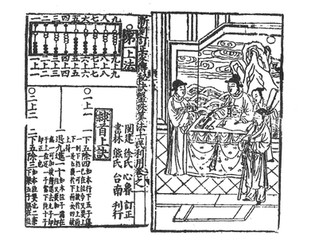

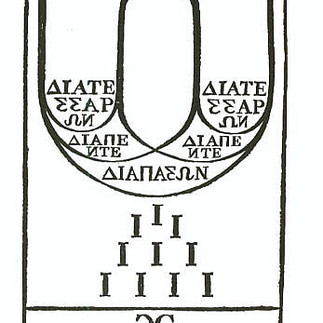

My aim in writing 'Spelling Synergetics' is to communicate one of the core lessons from David Abram's book, The Spell of the Sensuous. What I learned is that the phonetic alphabet is a technology. The ABCs we learned as children originated from a primordial split between humans and the more-than-human world of Nature. Marshall McLuhan analyzed the ancient paradigm shift of this technology in terms of visual and acoustic space. In Part 1, I claimed that there is a phonetic technology operating in Synergetics that has more to do with acoustic space itself than with the audible phonemes of spoken language. I proposed to focus on a single illustration from Synergetics: a diagram that Fuller titled 'Underlying Order in Randomness'. I'm certain that Fuller's chart - one of his most important ever put on paper - is an abacus. This post investigates the semiotic structure of the abacus. To that end, I've prepared this note to the reader:

The Synergetic Abacus

(redesign by Casey House)

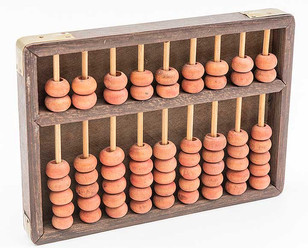

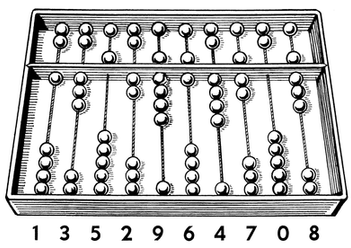

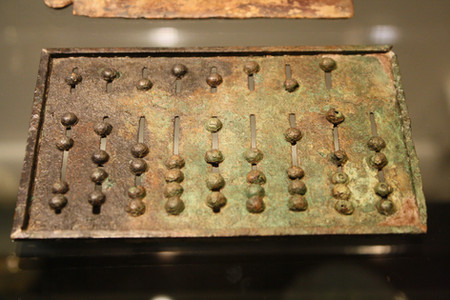

The abacus is an ancient tool for making calculations, named for its origins on a board of dust or sand. An abacus has moving beads that serve as the units for these calculations. Fuller's diagram apparently discloses the hidden order within randomness, which sounds approximately like 'making a calculation'. But this diagram doesn't appear to be an abacus - it's not moving! How could it move? It's a fixed image of figures and numbers on a screen (or page). Besides, do we even need this chart once its equations have been memorized? An abacus is a tool that can be used repeatedly to meet specific needs. Does the synergetic abacus meet the need for finding order in chaos? The complexity of the device is irrelevant; we are seeking to know its causal mechanism (from its basis in visual space). I am claiming that the figures in this diagram have something to do with the dynamics of acoustic space and are therefore closer to a sound wave than a Euclidean postulate. This is hardly obvious and escaped my attention for many years. In Part 1, I described the synergetic abacus as Fuller's 'drawings in the sand'. How could sand-drawings become sound? How can a figure in visual space transcend its boundaries and enter the kinetics of acoustic space?

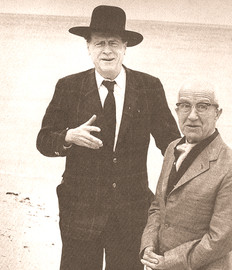

In the opening 3 minutes of this interview, Marshall McLuhan states that Bucky's ideas are directly connected to this dichotomy of visual and acoustic space. Marshall and Bucky were friends but the only comparative study I've found of their work is rather biased towards McLuhan's romantic view of poetry and literature. What's missing (and this applies to Fuller studies more generally) is mathematics. We must use numbers in order to understand Bucky. McLuhan was a classical 'man of letters' who was mainly focused on the Trivium: rhetoric, grammar and dialectic. It's interesting to learn that he started off as an engineering student, "because of my interest in structure and design." Bucky preferred working with the Quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, harmony and astronomy. He also claimed that McLuhan had no original ideas and admitted it! Their relationship was a union of opposties in many ways but was certainly a testament to the seven arts of liberal education. McLuhan used language in a renegade fashion ("I don’t necessarily agree with everything I say") while Bucky spoke earnestly and was never occult. Both men saw over-specialization as serious cultural problem; their agreed solution was friendly co-operation. Their synergy must have been remarkable.

McLuhan always emphasized how electric circuitry had accelerated our society into a post-literate age. He argued that we were becoming increasingly sceptical of literacy. Then he would explain how our educational techniques - using numbers for math and words for sentences - necessarily depend on visual space. He recognized that literacy requires books, projectors and blackboards, which are all technologies that promote a distinct 'bias of the eyes'. Radio, television and the internet have been weakening that bias by restoring an acoustic equilibrium to our senses, thus obscuring the value of literacy as a social 'good'. I'm re-hashing McLuhan here because the synergetic abacus appears to belong to the old-fashioned technologies of visual space. It presents itself in the same medium as paper, papyrus and computer screens. But there's something special about Bucky's diagram that is distinctly phonetic and connects our senses all the way back to the invention of the alphabet. This brings us into McLuhan's territory, where we can discover a beautiful harmony with Bucky's (or so I hope to demonstrate). Playing their melody requires a method that is at once speculative, structural and cultural. Let's get into it.

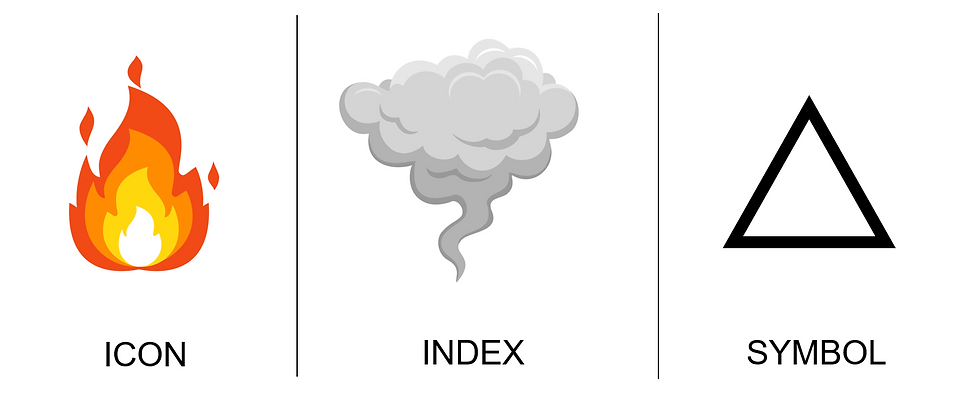

First, we need a bit of semiotics (the study of signs). Consider three different signs for fire:

Icons connect to their object by resemblance (look-alike)

Indexes have a hidden connection to their object (implication)

Symbols connect to their object by cultural custom (learned)

Semiotics gets complicated because signs can behave like more than one type. Icons and Symbols are notoriously interchangeable. For example, one could argue (like Plato) that the sharpness of the triangular figure resembles the searing heat of real fire, meaning that the alchemical symbol for fire (above) is more like an icon. However, the main feature of the synergetic abacus is the Index. Indexes are interesting because they always tell us more than they literally show us. Dark clouds are an index of rain because they imply the existence of rain without resembling or symbolizing actual rain drops. C.S. Peirce wrote that an index has "direct physical connection" with its object that "forces the attention to the particular object intended without describing it" (cf. Peirce on Signs, 1991). An index uses contiguity to direct our attention beyond its own figure, which is how it can signify an object without using resemblance (like icons) or cultural norms (like symbols). It's helpful to think of an index as a figure with a hidden ground. It is this 'occult' context that allows the sign to function as an index.

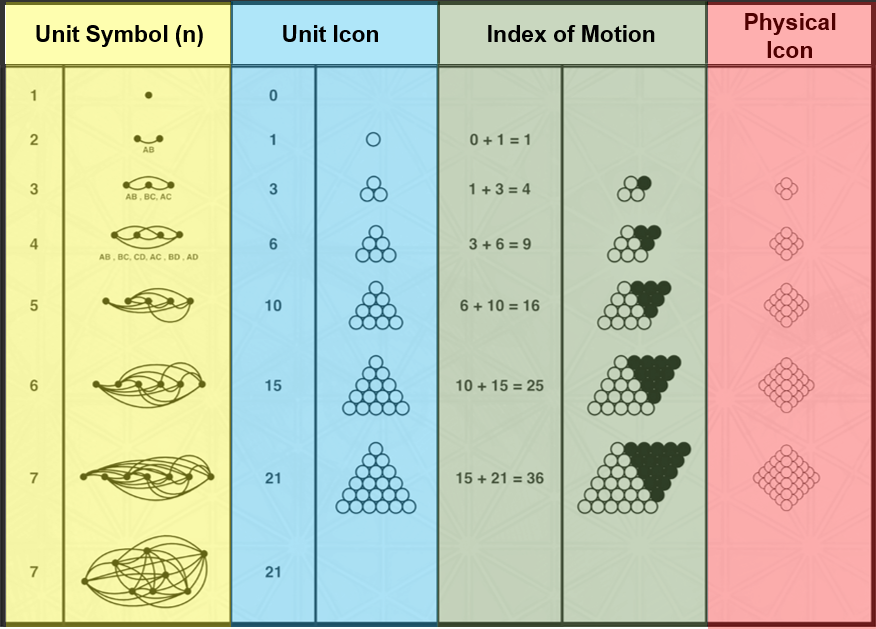

Now, onto the synergetic abacus. I will offer an overview of the entire device but will only be considering its indexes in this post. The abacus has 3 pairs of columns, each with numbers on the left and figures on the right and one final column (red) that contains only figures (no numbers). The numbers are symbols and will be ignored for now. My colour-coded titles apply to the geometric figures:

Unit Symbol: a variable input of a discrete quantity (n)

Unit Icon: the beads of the abacus

Index of Motion: the motion of these beads in the process of performing a calculation

Physical Icon: the model produced by the calculation (video credit: Struppi)

I am not claiming that an index of motion is the same as motion (anymore than I would claim that smoke is fire). My claim is that the figures in the green column have a hidden ground that implies the existence of motion. The video above shows how the unit icons, like the beads of an abacus, have a physical or structural order requiring certain units to be moved prior to other units. The green column on the synergetic abacus indexes these motions by combining unit icons from the blue column. For example, the index of n=6 places its unit icon adjacent to the unit icon for n=5 (drawn solid black). So each index shows which units have already been accounted for in the process of a calculation. This indexing of motion is therefore an indexing of calculation, which gives the synergetic abacus the semiotic structure of a conventional abacus but repesented on the flat plane of visual space. In other words, the synergetic abacus indexes motion using geometric figures. But recall that indexing requires a context or ground in order for signs to function as indexes.

Things are starting to get complicated but this is really important. To understand the dynamics of the synergetic abacus, we need to do more than study its arithmetic and geometry. The indexical function of signs is related to psychology and linguistics - areas that McLuhan knew well. Maybe he can tell us if there is any fire under all this smoke.

NOTE: The distinction between Figure and Ground is central to McLuhan's theory of culture and technology. He adapted it from Gestalt psychology. 'Figure' refers to something that jumps out at us, something that grabs our attention. 'Ground' refers to something that supports or contextualizes a situation, and is usually an area of unattention. To learn more, play this module.

from The Laws of Media (1988)

The left-hemisphere paradigm of quantitative measurement and of precision depends on a hidden ground, which has never been discussed by scientists in any field. That hidden ground is the acceptance of visual space as the norm of science and of rational endeavour. p.110

Visual space is a man-made artefact, whereas acoustic space is a natural environmental form. Visual space is space as created and perceived by the eyes when they are abstracted or separated from the activity of the other senses. With respect to its properties, this space is a continuous, connected, homogeneous (uniform), and static container. Visual space is man-made in the basic sense that it is abstracted from the interplay with other senses and their specific modes. This abstraction occurs by the agency of the phonetic alphabet alone: it does not occur in any culture lacking the phonetic alphabet. The alphabet is the hidden ground of the figure of visual space. p.22

I'm going to use McLuhan's Figure-Ground distinction to give a more straightforward definition for an index. Consider my definition before moving on with the rest of this post. The word 'occult' simply means 'hidden' or 'concealed':

Indexes are figures that carry us into their ground.

The sign grabs our attention (as figure)

then directs our attention to its object

in the hidden ground of unattention.

An index is a sign with an occult meaning.Everyone learns their ABCs but not everyone learns their אבג. In both cases, phonetic alphabets have been visualized as letters; "static structure[s] that could be diagrammed, or a set of rules that could be ordered and listed." (Abram, p. 87). Despite this shared definition, English and Hebrew remain culturally distinct within 'Western culture' as a whole. This is why letters and numbers are symbols, since they have to be learned (although ancient Semitic letters have iconic origins). Whether you know the Hebrew 'aleph-beth' or not, it has traditionally been honoured because "the ancient Hebrews were among the first communities to make sustained use of phonetic writing, the first bearers of an alphabet." (Abram, p.144) When we talk about 'the alphabet', we are distinguishing a phonetic technology that first appeared and proliferated in the form Hebrew. Biblical Hebrew is studied at four levels of interpretation known under the acronym ParDES. I would compare the occult meaning of an index to the level of 'Remez' (רֶמֶז); hints of hidden or allegorical meaning.

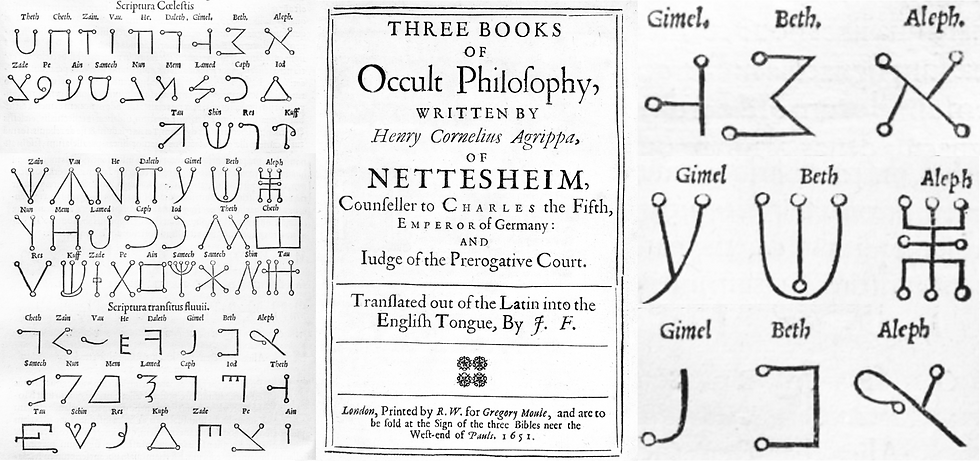

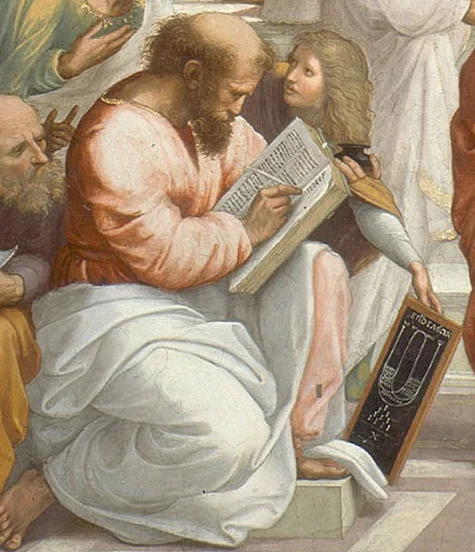

The occult significance of the Hebrew alphabet was popularized in the Renaissance when philosophers like Pico della Mirandola synthesized Jewish and Christian religion with Greek and Hermetic wisdom. This enlightenment brought the semiotics of Hebrew into greater focus. A new form of inquiry began on paper, i.e. within the confines of visual space. It belonged to a broader syncretic vision of philosophy based on prisca theologia, promoting a cultural reconciliation between Athens and Jerusalem. Theoretical barriers between magic, religion, science and art seemed to evaporate. Philosophers were motivated to seek the truth wherever it led, sometimes at the cost of their reputations or their lives. Today, we refer to this movement as Western Esotericism. Below are examples (from an influtential esoteric work) of how the Hebrew alphabet was being drawn out of its hidden ground and merging with geometry. Disclosed as 'Celestial alphabets', this approach was effectively speculative, structural and cultural. It indicated a deepening exploration of (and bias for) visual space, no doubt stirred by the relatively new Gutenberg Press.

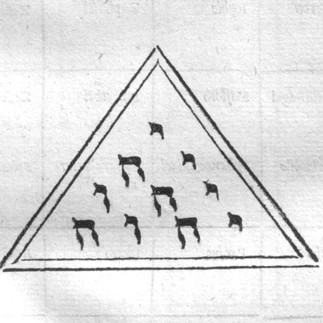

It was along these lines that geometry and the alphabet began their dance between figure and ground. Consider the images below, where the four letter name for God (the Tetragrammaton) is arranged in the order of the Pythagorean tetraktys. The Tetragrammaton indexes the tetraktys and the tetraktys indexes the Tetragrammaton; a visual translation between the Book of Nature and the Book of Scripture. When one is brought to our attention, the other recedes into the background. McLuhan's claim is reversible. Figure and ground are relative and can change from moment to moment, just as our attention is constantly shifting. Hence it is simpler to speak of signs and indexes when discussing images like these, since an index can only function together with its ground. An index primes our attention to seek its ground as the structural context of the figure we are seeing in visual space. Of the many works associated with Western Esotericism, I'm interested in the images described as alchemical or hieroglyphic, meaning that their indexing is recursive. Ground gives way to figure gives way to ground...

In my essay "What is Synergetics?", I described Synergetics as 'conceptual technology'. Let me refine that description: Synergetics enhances literacy, which is to say that it enhances our conceptual awareness of visual space. It does this by retrieving 'cultural' indexes, such as alchemical pictures from the Renaissance and Early Modern period. One of the most important mechanisms for this retrieveal process is the indexing of motion on the synergetic abacus. I've communicated a key insight in this post that was gleaned from the intellectual harmony between Bucky and his friend Marshall: the alphabet itself is an underlying order in randomness. But it is also a phonetic technology that opened up a new distance between humans and Nature. If we can understand the dynamics of the synergetic abacus, then this 'key' will bring Synergetics to our attention (as figure) against the hidden ground of Western civilizations as literate civilizations. Such a comprehensive view may only be attainable in a post-literate society that has learned the true meaning behind Fuller's discoveries.

If you are still confused, play this module and then read my post again.

Part 3 to come.

About the Author:

Dante Diotallevi is an independent scholar living in Canada. He holds a BSc. in Biology and an M.A. in Philosophy from Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario.

Comments